|

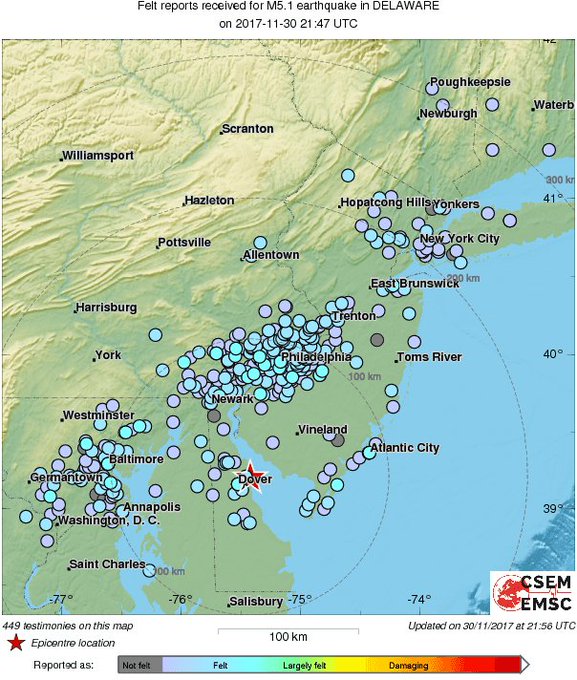

| THE EPICENTER OF THE NOVEMBER 30 QUAKE. USGS |

Something rather strange happened in Delaware yesterday: the ground shook.

At around 4.47pm local time (9.47pm GMT), an earthquake registering as a 4.1M hit within the Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge, at a relatively shallow depth of 8.1 kilometers (5 miles). The tremors were felt in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, Virginia, and Washington DC.

Earthquakes do happen in this part of the world, but ones this powerful are exceedingly rare. The last time Delaware experienced anything comparable was way back in 1871 when another 4.1M quake shook the state.

As plenty of you know, earthquakes are most commonly associated with fault lines, particularly those along tectonic plate boundaries. Plates sliding across each other (e.g. the San Andreas Fault) and plates subducting beneath another one (e.g. the Cascadia Subduction Zone) are where most major earthquakes occur, as their movements permit the most extreme build ups of stress.

The section of North America east of the Rocky Mountains, however, doesn’t have any tectonic boundaries – so what caused the Delaware earthquake?

Technically, it’s known as an intraplate earthquake, one that occurs in the middle of a tectonic plate. A region famous for such quakes is the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ), one that’s centered on southeast Missouri. Again, there are no tectonic boundaries here, but there are ancient faults that some have referred to as “mantle scars”.

The NMSZ’s origins can be traced back to the attempted split of the continental landmass we now see as the contiguous United States. Although this severance never succeeded, old faults remained, and every now and then, they slip. Between 1811 and 1812, for example, several earthquakes struck the region, with one possibly as powerful as a 7.7M event.

Ancient fault networks streak through the area east of the Rocky Mountains too, and although they aren’t as hazardous as those in the NMSZ, they can slip from time to time. The North American Plate experiences external forces from surrounding plates all the time, and this can sometimes get transferred to these quiet faults, causing them to become temporarily active.

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), in a statement, explained that “most earthquakes in North America east of the Rockies occur as faulting within bedrock, usually miles deep.”

They point out, however, that few of the region’s faults “are known to have been active in the current geologic era,” adding that “few earthquakes east of the Rockies… have been definitely linked to mapped geologic faults.”

It's possible, of course, that it was caused by a fault that we have yet to discover.

“There are faults in the subsurface in a lot of places, and they’re not necessarily known,” geophysicist Randy Baldwin of the USGS National Earthquake Information Center in Denver, told IFLScience.

“These old basement faults can reactive from time to time; they get stressed and they can create periodic earthquakes,” he added.

One tantalizing additional possibility resides in a study published back in 2016. Seismic imaging techniques revealed that pieces of the underside of the North American Plate are breaking off from time to time and sinking into the lower mantle. This leaves the remaining plate thinner than it was before, which makes it less rigid and more prone to slipping.

This was touted as a possible explanation for the 5.8M earthquake that shook Virginia back in August 2011, a region that hasn’t been seismically active for a very long time. Could the same effect have caused the Delaware quake?

The USGS also mentions “induced earthquakes”, those caused by human activity. Fracking, and primarily wastewater disposal, are the reasons why there has been a huge uptick in induced tremors in the US recently. It’s hinted that this could be behind the recent Delaware quake, but there’s no evidence for this just yet.

0 comments:

Post a Comment